1998-2002 Drought

Beginning in 1998, many areas in the Carolinas experienced several years of below-normal precipitation: precipitation deficits over the next four years were among the largest ever recorded. The meterological drought quickly became an agricultural one: farmers and foresters were particularly affected. The prolonged duration of the drought had severe hydrological effects, with the cumulative shortfall of precipitation resulting in record lows for streamflows, groundwater levels, and reservoir storage.

[L]ow water levels on Lake Wylie forced organizers to cancel a fishing tournament that had been planned for later this month. That will mean the loss of an estimated $200,000 in motel reservations and banquet events, a York County tourism official said."

Bruce Smith, AP, "Heavy Rains Help, But Drought Persists," September 4, 2002

Agriculture

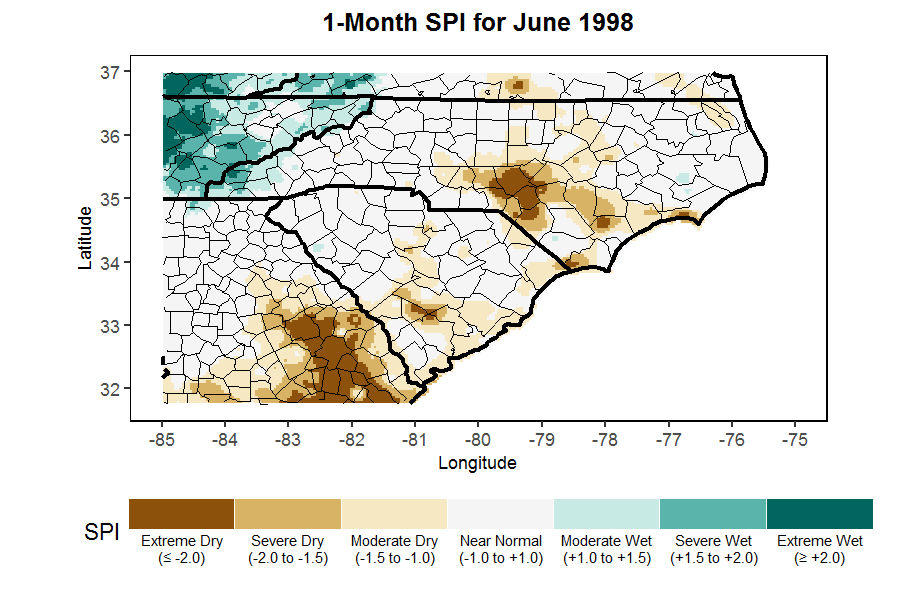

The drought began early in the summer of 1998, and farmers in the Carolinas felt its impact immediately. Not only was June dry, in South Carolina it was marked by weeks of 95-degree-plus days. By the first of July, South Carolina officials had already declared an "incipient drought" — the first level of four drought stages — in effect for the state [1].

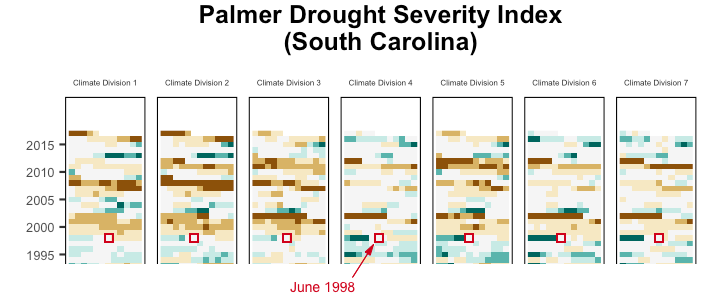

The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), one of the commonest measures of drought and one designed to show overall moisture conditions, wouldn't yet show signs of a drought as the spring had been relatively well-timed.

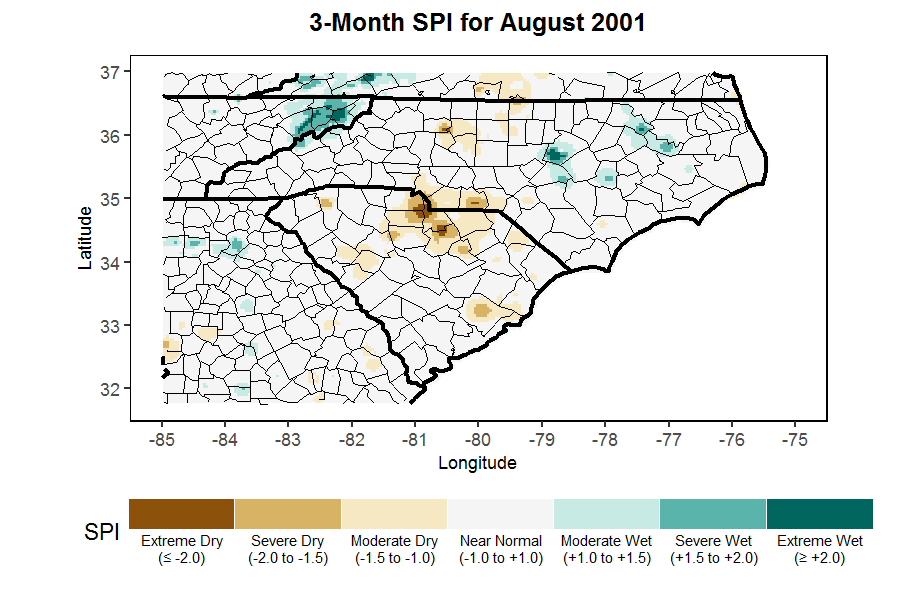

But the Standard Precipitation Index (SPI), based on precipitation only, provided an early indication of the drought's presence.

The timing of precipitation can be as important as the total amount. Corn, for example, needs rain especially in its early vegetative stages through the silking period.

Two photographs of corns fields in Hemingway, SC, taken during the summer of 2002 show the difference well-timed if scanty precipitation can make. The early crop (left) is stressed but may have received enough early rainfall to have made it; the crop planted later (right) didn't.

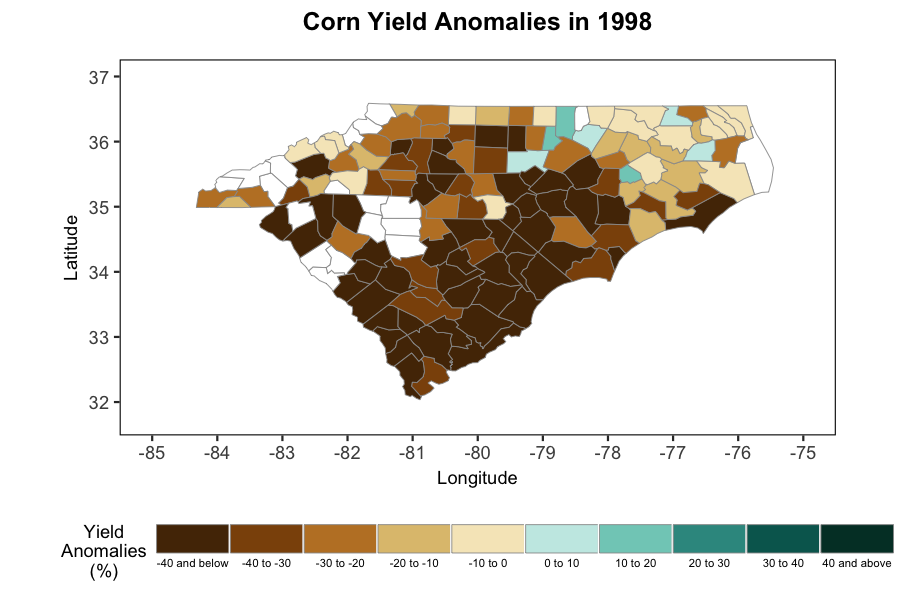

The dry June of 1998 coincided with crucial growing stages of the corn crop, and substantially reduced yield.

"Corn is beyond help," Agriculture Commissioner Les Tindal said Tuesday. He expects less than half the state's corn crop to survive.

"If it rained three inches today, tomorrow and the next day, corn would not come back. It's over with," Tindal said.

"S.C. Corn Crop 'Beyond Help' in Drought", The State (Columbia, SC), July 8, 1998

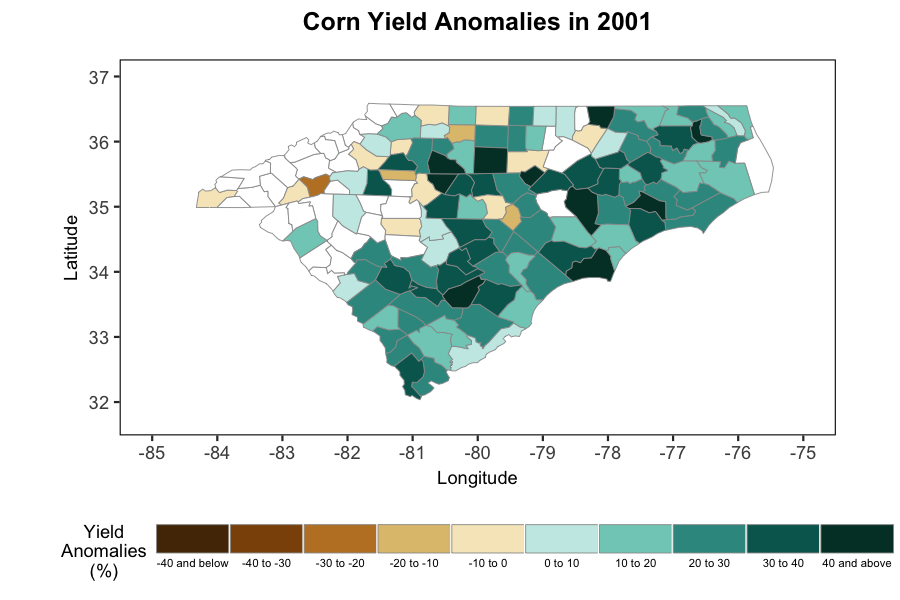

In 2001, timely rainfalls kept the agricultural drought at bay. Although not enough rain fell to raise streamflow and groundwater levels, there was enough to provide moisture to the top soil layers, and minimize crop losses [2].

Irrigation could be used to overcome the shortfall — at least for a while. But the drought's prolonged length meant that those resources were being depleted or becoming costly. Ponds shriveled and wells ran dry. New, deeper wells had to be dug. As the drought wore on, well-digging companies did a booming business.

Well drillers can't punch holes fast enough, and an irrigation company is running its water wagons seven days a week....

"Business is skyrocketing. We're struggling to keep up," said Alfred Kiesling Sr., owner of B&K Well Drilling in Mooresville. His three well-drilling rigs can't keep up with demand, which has grown 20 percent from last year.

Ellison Clary, "With Land Dry, Some Charlotte, N.C.-Area Businesses Blossom," The Charlotte Observer, August 16, 2002

Sod farmers and nursery farmers found themselves in a double bind. Not only were they having to pay more to irrigate their land, but demand for their products was down. No one wants new landscaping when water bans forbid residents from turning on their sprinkler systems [3].

Forestry

With 12 million acres of trees, South Carolina has lost about 13 million trees in 25 counties.

Charles Seabrook, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 14, 2002

The drought presented multiple threats to the forestry industry. The prolonged dry conditions increased the possibility of fire, and the stressed trees were that much more susceptible to disease. The SC Forestry Commission estimated the total impact of the drought at more than $1.3 billion dollars [4].

In July 1998, SC State Forester Hugh Ryan declared a ban on outdoor burning, the state's first since 1994 [5]. Burning bans were imposed regularly over the next four years, but with the dry underbrush, fires were inevitable. On August 25, 1999, the Charleston Post and Courier reported that the state was fighting about 100 lightning-strike fires each week. In 2000, North Carolina wildfires scorched more than 9,600 acres, including more than 6,300 acres in the Linville Gorge, a federal wilderness area [6].

Over the past year, the forestry commission has responded to 6,000 wildfires that burned over 52,000 acres, [Ken Cabe, spokesman for the S.C. Forestry Commission] said. That compares with the state's 10-year average of about 4,700 wildfires per year, burning close to 27,000 acres.

Caroline Brustad, As South Carolina Heads into Its Fifth Year of Drought, Local Residents Wonder When the Rain Will Return," The Herald (Rock Hill, S.C.), July 21, 2002

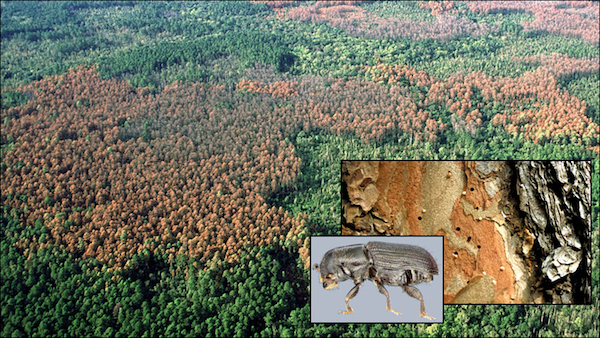

But fires weren't the only threat forest faced. The drought made forests more susctible to the evergreen-killing southern pine beetle. The insect is considered the most destructive pest of pine trees in the South, leaving pockets of dead pines like brown scabs in the forest.

The Southern pine beetle has destroyed a record $220 million in pines in South Carolina this year. The perennial pest, shorter than a grain of rice, kills trees after it bores into the bark to lay eggs. Trees stressed by four years of drought can't summon the energy to fight back....

In a typical year,...the current epidemic of pine beetles might cause $50 million in damage to S.C. pines. But weakened by drought, the trees are easier victims and loss estimates rose to $220 million. While drought hasn't increased the numbers of beetles, which rise and fall in multiyear cycles, dollar losses have risen since 1995.

Bruce Henderson, "Beetle Infestation Causes $220 Million in Damage to North Carolina Pine Trees," The Charlotte Observer, September 29, 2002

Water Supply & Quality

Several locations in NC’s western Piedmont recorded 60-70 inch precipitation deficits over the four-year period, among the largest ever recorded [7]. Of the 211 continuous-record streamflow gaging stations in NC, 150 sites set record low annual mean discharge, and 121 sites set record daily mean discharge [8]. Further analyses confirmed that 1998-2002 established minimum flows of record for several sites in the Blue Ridge and Western Piedmont regions. Of 137 groundwater observation wells, 100 recorded record-low levels during water year 2002 [9].

Over the last four years, North and South Carolina have come up short by the equivalent of a year's supply of rain, and now cities like Charlotte and Raleigh, N.C., as well as dozens of smaller towns, are paying the price in the form of mandatory restrictions intended to reduce water use by as much as 20 percent.

Douglas Jehl, "Development and a Drought Cut Carolinas' Water Supply," New York Times, August 29, 2002

In South Carolina, Kiuchi reported below-average precipitation for water years 1999 (-5.68 inches), 2000 (-2.39 inches), 2001 (-10.96 inches) [10]. Rainfall shortages during normal recharge period (winter, spring) and few or no tropical systems during the summers produced steadily deteriorating hydrological conditions throughout 1998-2002 [11]. Data from monitoring wells at shallow and deep aquifers indicate an overall lowering of water levels during the period Kiuchii studied, and without adequate rainfall to replenish water supplies, streamflow and reservoir levels remained low throughout the drought. The most critical conditions occurred in summer 2002. In South Carolina, 8 of 14 unregulated streams (with records of 30+ years) set new low-flow records in 2002, and many reservoirs were below the target operating levels [12]. On July 24, 2002, the SC Drought Response Committee (DRC) designated 39 of South Carolina's 46 counties at the extreme level (the state’s highest level). One month later, all 46 counties were in the extreme drought category.

Some of the most critical conditions and impacts occurred in the Yadkin-Pee Dee Basin.

A PEE DEE EXAMPLE

Since last fall, the intake pipes for the Georgetown County water system have been plagued by salt water. Usually the fresh water from the Pee Dee and Waccamaw rivers keep the salt water at bay.

The plant usually has to wait for low tide to draw water in and has even closed a few times. Officials said they can turn to backup wells, but worry they can't provide enough water during peak tourist times. has even closed a few times. Officials said they can turn to backup wells, but worry they can't provide enough water during peak tourist times.

Jeffrey Collins, AP, "Pee Dee River Could Nearly Dry Up in Next Three Months," July 10, 2002

The detail here from the Palmer Hydrologic Drought Index (PHDI) for SC Climate Divison 4, through which the Pee Dee River flows, clearly indicates that the preceding 12 months were quite dry.

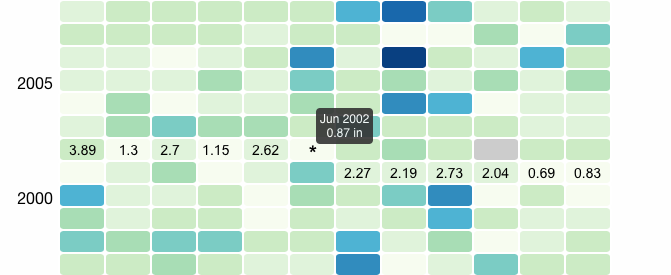

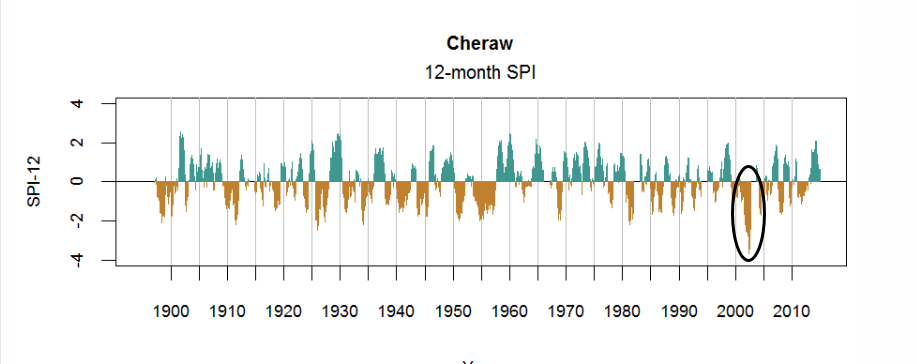

In the Carolinas, streamflows are sustained — largely — by groundwater discharge. Soaking rains in winter and spring normally replenish the groundwater, as well as contribute some surface runoff [13]. Examining this more closely by looking at the station data for Cheraw, SC. Cheraw — upstream on the Pee Dee — shows that the replenishing winter rains were absent in 2001–2002.

Comparing these amounts to what we might expect to get (Cheraw | Average Monthly Precipitation), we can construct the table below.

Monthly Precipitation for Cheraw

| Month | Normals (1981-2010) | 2001-2002 Amounts | % of Normal |

| Jul | 3.59 | 2.27 | 63% |

| Aug | 3.19 | 2.19 | 69% |

| Sep | 3.83 | 2.73 | 71% |

| Oct | 2.81 | 2.04 | 73% |

| Nov | 3.07 | 0.69 | 22% |

| Dec | 4.66 | 0.83 | 18% |

| Jan | 5.37 | 3.89 | 72% |

| Feb | 5.64 | 1.3 | 23% |

| Mar | 4.08 | 2.7 | 66% |

| Apr | 3.59 | 1.15 | 32% |

| May | 2.98 | 2.62 | 88% |

| Jun | 2.92 | 0.87 | 30% |

| 12 months | 45.73 | 23.28 | 51% |

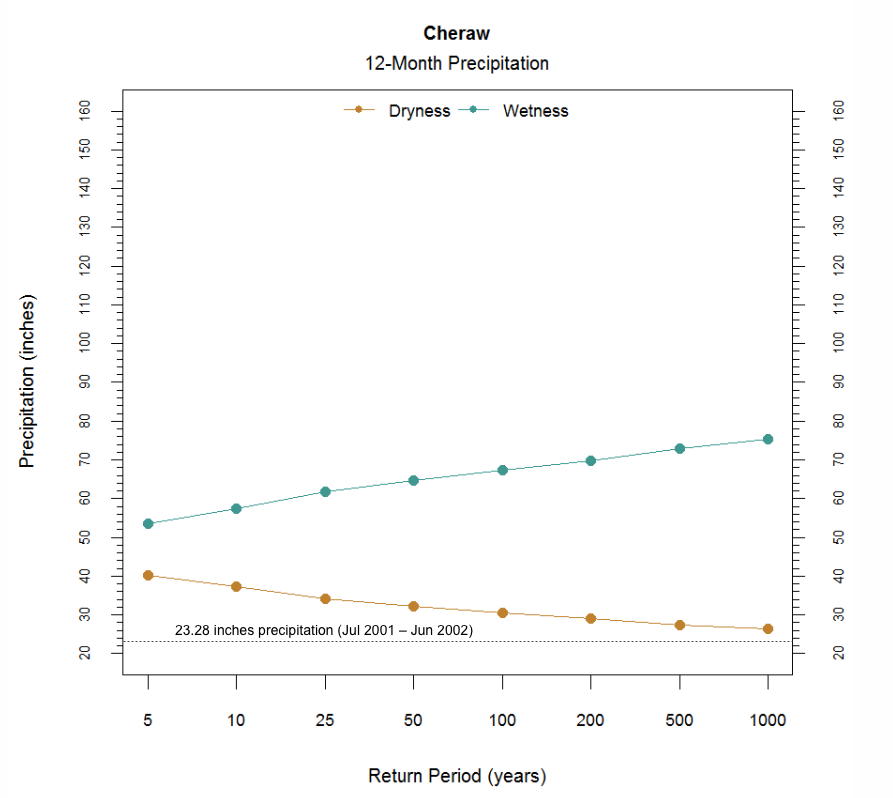

Cheraw received only 23.28 inches, or 51%, of normal rainfall for this 12-month period. However, how common is this? Plotting 23.28 inches on the 12-month precipitation recurrence interval chart for Cheraw shows that receiving so little rainfall is a very rare occurrence.

An examination of the Standard Precipitation Index confirms that this 12-month period was the driest on record for Cheraw.

The Catawba-Wateree system faced a situation as dire as that on the Pee Dee. Duke Power operated conservatively to sustain water resources in the Catawba-Wateree basin, but it acted independently and did not communicate the drought severity to water systems, municipalities, and the general public until it was nearly too late.

Duke painted a bleak picture of current conditions on its lakes....

Groundwater normally flows toward lakes and rivers, feeding them. Now it's reversed direction, absorbing water from the lakes. "We're talking about a groundwater table that's dropping out from under us as we talk," said ... Duke's hydro operations chief.

Bruce Henderson, "Duke Power Warns Towns in Charlotte, N.C., Area to Cut Water Use," The Charlotte Observer, August 28, 2002

By summer 2002 concerns about the security of water supplies prompted Duke to alert other stakeholders, but the lack of a communication system slowed those efforts. The importance of communication and cooperation was one of strongest lessons water managers learned during the 1998-2002 drought.

Notes

1. Shaundra Lee, "A Dry and Thirsty Land: S.C. Edging into Drought," The State (Columbia, SC), July 2, 1998. ↩

2. J. Curtis Weaver, 2005, The Drought of 1998-2002 in North Carolina—Precipitation and Hydrologic Conditions, USDOI/USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5053, p. 5. ↩

3. Brian Hicks, "When the Well Runs Dry," The Post & Courier (Charleston, SC), September 24, 2002↩

4. SC Department of Natural Resources, 2003, Annual Report: Fiscal Year, July 1, 2002-June 30, 2003, p. 13. ↩

5. Shaundra Lee, "A Dry and Thirsty Land." ↩

6. Margaret Lillard, AP, "Fires inch through wilderness deadfall in North Carolina," November 4, 2000↩

7. Weaver, 2005, p. 1. ↩

8. Weaver, 2005, p. 68. ↩

9. Weaver, 2005, p. 45. ↩

10. Masaaki Kiuchi, 2002, Multiyear-Drought Impact on Hydrologic Conditions in South Carolina, Water Years 1998-2001, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, March 2002, p.2. ↩

11. Kiuchi, 2002, p. 2. ↩

12. SC Department of Natural Resources, 2004, Hydrologic Effects of the June 1998-August 2002 Drought in South Carolina, Water Resources Report 34, p. 41. ↩

13. Kiuchi, 2002, p. 2.↩